Just before midnight on May 30th, 1973, the American Export-Isbrandtsen Line containership Sea Witch and her crew of 33 slipped her lines at the Howland Hook container terminal on Staten Island and made for sea, destined for Puerto Rico and points beyond with a load of 730 containers above and below her decks. Built by Bath Iron Works in 1968, the ship had traditional two-house style with a small forward superstructure housing her bridge and officers quarters and and a rear superstructure atop her engineering spaces that housed the majority of the crew. Though she would be considered small by today’s standards, Sea Witch was the largest vessel ever built in the State of Maine to date, with a length of 610 feet and a total capacity of 928 TEU. Initially under the command of a Moran Tug Company Docking Pilot and escorted by a pair of Moran tugboats from the dockside to a point off of New Brighton, Staten Island, the Sea Witch came under the command of Sandy Hook Pilot John T. (Jack) Cahill at 12:23AM on May 31st as the docking pilot disembarked and the ship shaped a course for St. George.

Ordering an increase to full harbor speed of 13 knots at 12:29AM as the ship passed the ferry terminal at the tip of St. George, Cahill, who was joined in the compact bridge by Sea Witch’s Capt. John Paterson and three other members of the vessel’s crew, ordered the helmsman to bring the ship to a heading of 167 degrees in order to begin transiting the Narrows. Riding an approximately 2 to 3 knot ebb tide as it poured through the Narrows, Sea Witch was moving at actual speeds closer to 15 knots when at 12:36AM Cahill ordered a course correction to 157 degrees as the ship began to pass the general anchorage at Stapleton.

The second turn never occurred. When the ship did not respond as expected, the helmsman advised that Sea Witch was no longer steering. Paterson attempted to correct the problem by transferring steering control from the starboard to the port steering system while Cahill also took corrective action ordering hard left rudder, but the attempts by both Captain and Pilot proved futile. As designed, both the port and starboard steering control units on Sea Witch fed into a single mechanism controlled by a faulty “key”, a device similar to a cotter pin, which had failed and worked loose. Without this small piece in place all steering control from the bridge was lost, and very quickly Sea Witch was steaming out of the channel toward Staten Island.

Cahill immediately ordered the engines to full astern and the crew of three sailors stationed on the bow to let go the port anchor, while also sounding a series of short rapid blasts on the ship’s whistle to signal that Sea Witch was in distress to vessels in the area. Watching as the bow crew worked feverishly to release the port anchor only to be defeated by a jammed pawl, Paterson sounded the general alarm aboard the ship as the bow crew shifted to the Starboard anchor, which despite being made free to run from the windlass would not drop. Seeing that his ship was now a mere 200 feet from an anchored oil tanker and had no hope of stopping in time to avoid a collision, Cahill locked the Sea Witch’s whistle to sound continuously and all crew quickly abandoned the forward superstructure.

The tanker Esso Brussels, shown early in her service career with the Esso Oil Company. Photo from www.aukevisser.nl/

As the events on the Sea Witch were playing themselves out, the fully-loaded oil tanker Esso Brussels lay anchored in the southernmost Stapleton anchorage area just above of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Carrying 319,402 barrels of light Nigerian crude destined for Exxon’s Bayway Refinery, the 1960-built Esso Brussels was a 25,906 gross ton, 698 foot ship built in a similar two-house style as the Sea Witch. Under the command of Captain, Capt. Constant Dert, the ship had a mixed European crew of 36 men and one woman aboard ship in the early morning hours of May 31st, when the unmistakeable staccato of the maritime danger signal from the Sea Witch caught the attention of the Mate standing watch on her bridge. Easily sighting Sea Witch as she began to turn towards his vessel from the navigation channel, the Mate initially thought the ship would pass astern of the Esso Brussels, but as the approaching vessel continued to turn towards his and showed no signs of stopping, he sounded the general alarm.

Less than five minutes had passed since the crew aboard the Sea Witch realized she was out of control before she, still making about 13 knots with her engines in full reverse, slammed into the Starboard midship of the Esso Brussels roughly dead-center between her deckhouses and piercing three fully loaded cargo tanks. As dazed crews aboard both ships struggled to regain their footing following the impact, a chance spark from either grinding metal or a severed electrical line found its way into the heavy spray of oil mist blasting out of the tanker onto both ships and the night exploded.

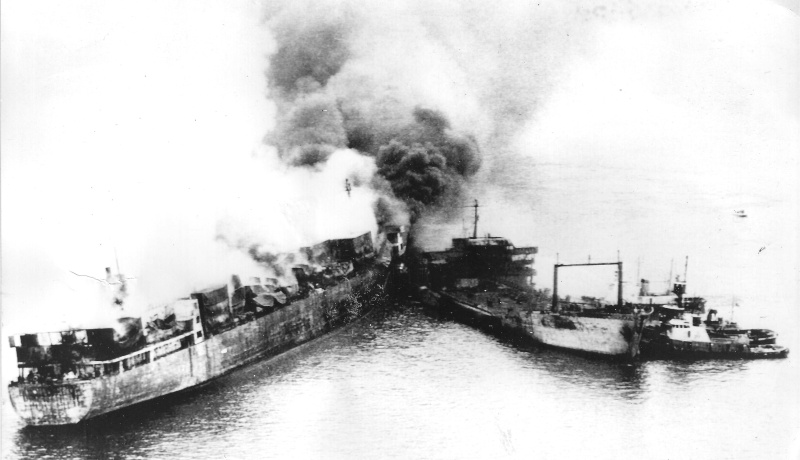

A photographer in Gravesend, Brooklyn snapped this shot of the fire resulting from the collision of the Esso Brussels and Sea Witch.

From the Marine 9 station at the Staten Island Ferry Terminal, the Fire Fighter was slightly over a mile away from the collision site when a massive fireball erupted from the vicinity of the Esso Brussels at 12:40AM. Immediately reporting the sighting to division headquarters and wasting no time to get underway, Fire Fighter and her small crew commanded by Lieutenant James McKenna stood out alone to combat a fire which had spread atop a rapidly growing oil slick to cover nearly 3,000 yards of water surface around the Esso Brussels. After circling the massive pool of fire looking for survivors and finding none, she took a position on the Port bow of the tanker and using her bow monitor began to deluge the ship from an upwind and upcurrent position.

This rare color photograph of the moments after the collision of the Esso Brussels and Sea Witch also shows Fire Fighter at the extreme right and just outside of the burning oil slick as she took position to begin working the fire.

Aboard the Esso Brussels Capt. Dert mustered his crew on the aft Port side as far away as possible from the inferno raging midship, and supervised the crew as they lowered the aft Port lifeboat only to have trouble releasing it from its lines. Once freed from the ship, a mate tried to turn a hand crank to start the engine but the lifeboat was overloaded with terrified crew, making the task impossible. A last-second attempt to row away from the advancing fire was thwarted by the engines of Sea Witch, still running in full reverse, which were pulling both ships down the Narrows despite the resistance from the anchor of the Esso Brussels. This movement created a suction force which pinned the lifeboat against the tanker’s hull and brought the pool of flaming oil around the Stern and towards the lifeboat. Left with little option, the crew jumped into the water and swam for their lives in a desperate hope of escaping the approaching flames.

The situation was no better aboard Sea Witch, as the huge amount of burning oil spilling out of the Esso Brussels had completely encircled the ship and sealed off any chance of escape for the crew which had been forced to seek shelter in a small cabin in the aft superstructure. As the fire spread from her superstructure aft into her load of containers, it began to set off numerous containers filled with aerosol cans, welding gases and paint, causing numerous explosions that filled the air around the ship with projectiles and shrapnel. The crew would remain in this room for over an hour and a half enduring heat, pressure and hundreds of close-quarter explosions from the cargo.

With both ships locked together from the force of the impact, afire from stem to stern and now completely surrounded by a sea of burning oil, the still-operational engines of the Sea Witch combined with the outbound tide to drag the ships towards the middle of the navigation channel under the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Flames from the burning oil rose so high that they reached the bottom bridge 228 feet above the water’s surface as the ships passed beneath, damaging some equipment and scorching paint off the underside of the structure. At roughly the same time, the Port anchor of the Esso Brussels lost purchase on the bottom and the two ships proceeded into outer New York Harbor and ran hard aground in Gravesend Bay.

After both ships grounded Fire Fighter moved into position to fight the oil fire from the Starboard side of Esso Brussels, using every monitor aboard ship and her full pumping capacity to knock back the flames on the furiously burning tanker. As they brought the fires on the forward superstructure under control and the tide pushed the burning oil pool away from the bow of the ship, the Stern of the Sea Witch came into view of the horrified crew aboard the Fighter. Up until this moment, there had been no indication that there were two vessels involved in the fire; the dark of night and thick black smoke had totally concealed the Sea Witch from view for over an hour. Moving quickly along the port side of the ship they began to pour water on the blazing container stack, hoping to find some evidence of the ships crew.

Grouping into a cabin which was outfitted with a half-inch fire hose, the crew of Sea Witch sprayed the bulkheads, deck and ceiling around them to stave off being baked to death by the heat. They watched in horror as the water evaporated into steam as it hit the walls being cooked from the outside by the intense fire. With two men unaccounted for and the situation rapidly worsening, the strain became too much for Captain Paterson, who suffered a fatal heart attack shortly after the vessel grounded. Sighting what appeared to be another vessel through the thick smoke, Pilot Cahill donned a water-soaked blanket and went out onto the weather deck and used a flashlight in a desparate attempt to signal the vessel. Sighted by Lt. McKenna aboard Fighter, no time was wasted in shutting down her water pumps and commanding all 3,000 horsepower of her Winton diesels to get the ship into position to attempt a rescue of the trapped men from the thick of the fire.

Unleashing her bow monitor at full capacity to cut a trail through the burning-oil covered seas lying between her and the Stern of the Sea Witch, Fighter motored straight towards the stricken vessel as her crew brought ladders forward. Electing to stop pumping once again to give the ship full maneuvering power, Lt. McKenna nosed up against the Port quarter of the burning vessel and held his ship firm as the burning sea closed back around her and containers spewed fire and embers onto the deck. Moving quickly and with little regard for their own safety, Fighter‘s crew rigged their ladders and began removing her crew, working in tandem with their fellow sailors to lower the body of Capt. Paterson aboard once all men were accounted for. With 32 men now crowding into the vessel, Lt. McKenna ordered the fogging monitors brought online to offer some protection to ship and crew as he backed the ship through the flaming seas to safety. Informing the FDNY Marine Division of her recovery, Fire Fighter made for the 69th Street Pier in Brooklyn where she offloaded the crew of Sea Witch into waiting ambulances.

The Sea Witch (left) and Esso Brussels (right) aground, afire and still locked together in this photograph taken the morning after the collision.

Fire Fighter (at right) onscene the morning after the collision.

By the time Fire Fighter had returned to the scene and rejoined the fight to save life and property, the life and death struggles of the ships’ crews had already come to an end. Thanks to the efforts of Fire Fighter, 31 crew and Sandy Hook Pilot Jack Cahill were recovered alive from the Sea Witch, while further up the harbor the commercial tugboat Grace McAllister had rescued eleven crew from the Esso Brussels from the waters near the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. A further nine crewmen from both ships were recovered by vessels Dorothy McAllister, Brian McAllister, Jane McAllister, Roderick McAllister, Texaco Fire Chief, USACE Sentry, NYPD Launch No. 1 & No. 8 and the motor vessel Nimrod by dawn on May 31st. When final musters were taken at area hospitals, the days grim toll became clear: 3 crew from the Sea Witch and 13 crew from the Esso Brussels had died in the accident.

By dawn on the 31st the majority of oil fires on the water and aboard the Esso Brussels were under control or extinguished, aided greatly by her sound construction preventing her undamaged tanks from leaking any of their contents in the collision and resulting fire. With the Sea Witch still heavily aflame and with her entire load of containers still burning, the decision was made to separate the two ships and reduce the risk of another oil fire. Pulled apart by the Grace McAllister, the still-burning Esso Brussels was attacked by the Fighter, McKean and Harvey and her fires quickly extinguished, allowing the ship to be towed to the Military Ocean Terminal at Bayonne to have the balance of her oil cargo removed onto barges for delivery.

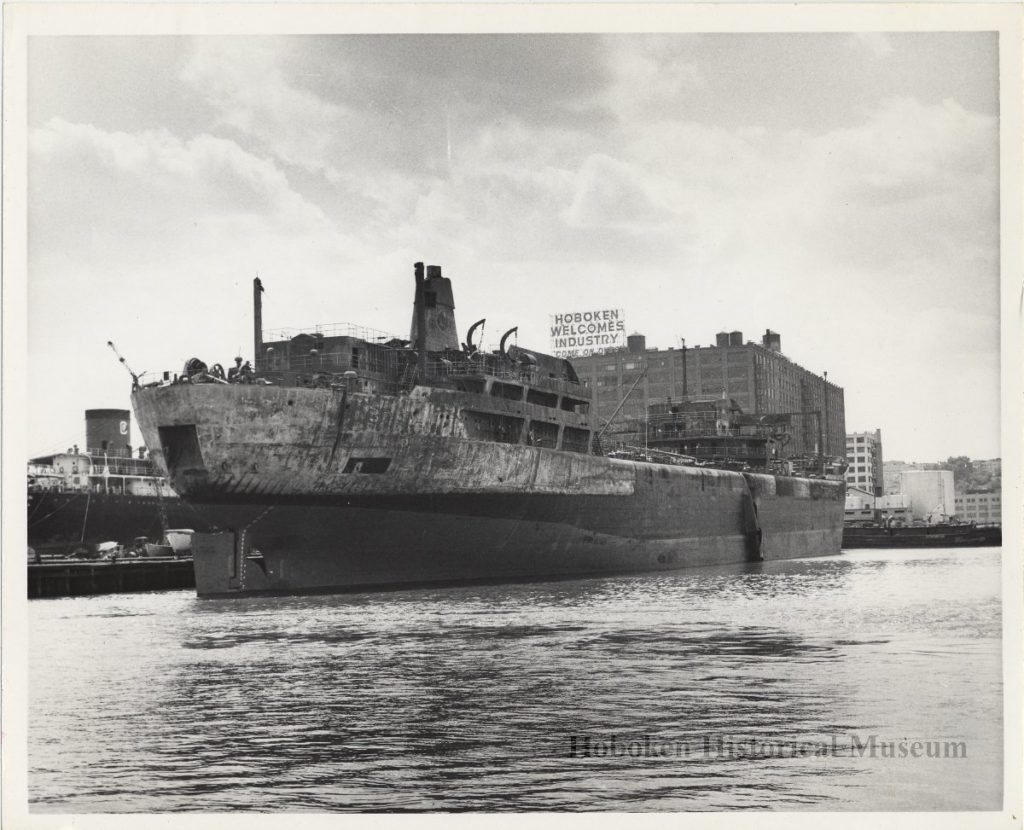

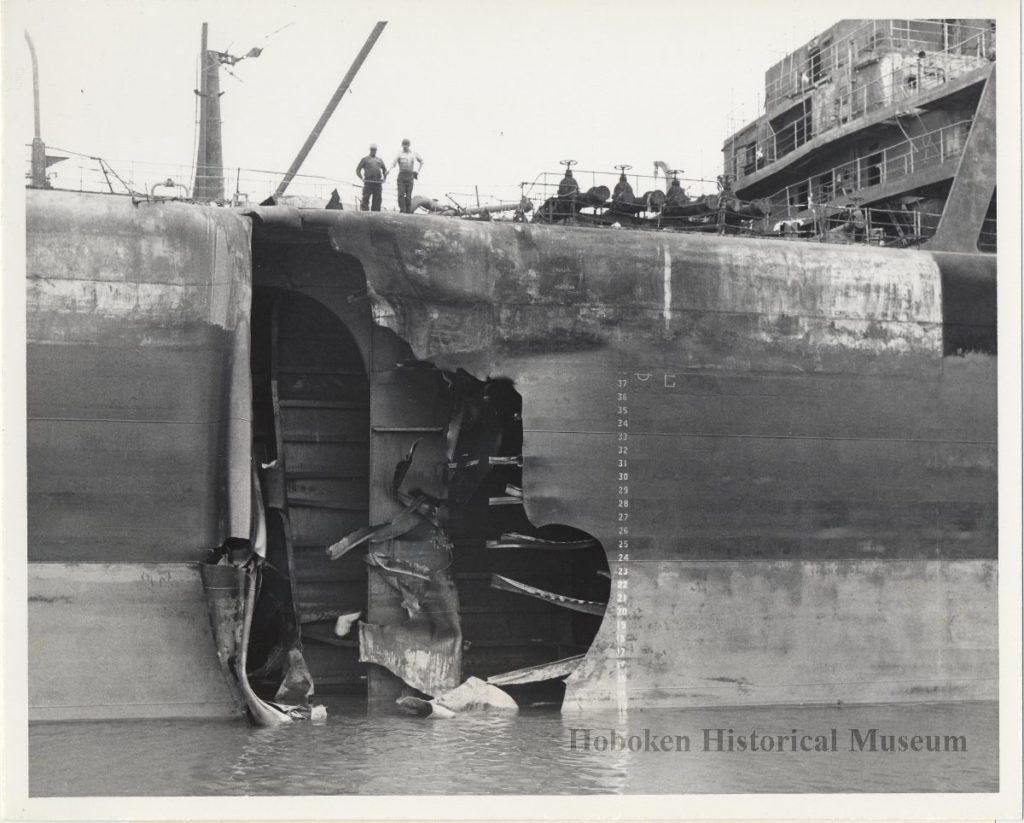

The Esso Brussels at Bayonne following the accident and fire, with a gaping hole in her Starboard side. Photo courtesy of the Hoboken Historical Museum.

A close-up of the gaping hole left by the Sea Witch in the hull of the Esso Brussels. Photo courtesy of the Hoboken Historical Museum.

As for Sea Witch, once the two vessels were separated the four onscene fireboats took up positions on the four corners of the burning vessel and began “surround and drown” operations aimed at quickly smothering the fire with massive amounts of water. While seeming to have an effect on the topside fires, the effort caused the Sea Witch to develop a 25 degree list which put the ship at risk of capsizing. After conferring with her owners, the Coast Guard and FDNY agreed to reduce firefighting efforts to a single fireboat onscene, releasing the Fire Fighter, McKean and Harvey from the scene. Fires would continue to burn aboard the Sea Witch for thirteen days before being officially declared out on June 14th, allowing her to be pumped out and towed to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for salvage and disposition.

The burned-out hulk of the Sea Witch rides at anchor in Gravesend Bay after all fires were declared out and salvage operations had begun. Note the large piece of her bow bent inward from the collision with the Esso Brussels.

In the days, weeks, months and years following the tragedy that occurred in the early morning hours of May 31st, 1973, each of the ships principally involved found their ways to different fates. Esso Brussels remained in Bayonne for over a year before being purchased by a Greek shipowner who towed the ship to Europe where she was refurbished and returned to service as the Petrola XVII. After sailing for a number of owners under different names, she ended her career in 1985 and was subsequently scrapped. The Sea Witch languished in her sad state at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for eight years as numerous legal battles were fought over the accident. Eventually, her hulk was sold to an American shipbuilder who utilized her less-damaged Stern superstructure and engine room in the construction of a Chemical Tanker, which sails today as the Chemical Pioneer and is a regular visitor to New York Harbor.

For their roles in the response and rescue of imperiled crewmen during the unfolding disaster, Fire Fighter and the commercial tugs Grace McAllister, Brian A. McAllister and Texaco Fire Chief were all decreed by the US Department of Transportation to be Gallant Ships for their actions. For his role in command of the Fire Fighter, Lt. McKenna was awared the Merchant Marine Meritorious Service Medal, and the crew of Fire Fighter were awarded the 1974 Merchant Marine Seamanship Trophy.

The only fireboat to have been so honored in the history of the United States, the full text of Fire Fighter’s citation is as follows:

In New York Harbor, June 2, 1973, the C/V SEA WITCH rammed the SS ESSO BRUSSELS, touching off explosions and fires. New York City FIRE FIGHTER, first fireboat to arrive on scene, concentrated her monitors on knocking down flames on the tanker, adrift in a sea of burning oil, when it became apparent that the bow of the SEA WITCH was embedded in the tanker amidship. The FIRE FIGHTER repositioned, thrusting deeper into the burning oil. While working aft around the containership, flashing lights were seen and shouts heard from men huddled on the fantail. All pumps were shut down to permit full propulsion. The FIRE FIGHTER made a port approach to the vessel and held her position as blazing containers threatened to topple and flames scorched the fireboat. Rapidly, the crew raised ladders against the burning hull. Thirty crewmen trapped aboard the SEA WITCH escaped to safety. The Master of the containership, who had suffered a heart attack, was lowered to the deck of the FIRE FIGHTER. After delivering the survivors to the Disaster Unit for treatment, the fireboat returned to continue bringing the fire under control.

The courage, expertise, and teamwork of her Commanding Officer, Pilot, officers and crew while exposed to personal danger in rescuing thirty-one seaman trapped aboard a burning vessel have caused the name of the FIRE FIGHTER to be perpetuated as a Gallant Ship.

Read the full US Coast Guard/NTSB Casualty Report by clicking HERE

Additional pictures and information on the Esso Brussels can be found HERE