The Greatest Single Threat: Fire Aboard the SS El Estero – April 24, 1943

From the August 2nd, 1945 NY PM Daily. Sourced via fultonhistory.com

The mission carried out by the Caven Point Army Depot in New Jersey was one of the best-kept secrets of World War II. Located landside on the border of Jersey City and Bayonne and sitting alongside the terminal rail yards of several major railroads, the Caven Point Army Depot was designed and built to serve as a large-scale port of embarkation for soldiers and war materials bound overseas. Equipped with a mile-long finger pier that extended out from the mudflats into Upper New York Bay to a point roughly next to Liberty Island, the port facilities could accommodate loading or unloading operations of up to four large troopships or cargo vessels at the same time. Heavily utilized during World War I as both a departure and return point for U.S. servicemen, Caven Point remained fully operational between the wars and readily assumed its role when America entered World War II.

An aerial view of upper New York Bay from over Staten Island and looking North towards Manhattan. The Caven Point Pier is visible in the center-left of the photo with four MSTS Troopships tied up at the pier. The Berthing location of the El Estero on the day of her fire is highlighted by the Red arrow. Pic courtesy of https://tugster.wordpress.com/

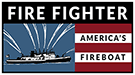

The outbreak of the World War II found the United States without a major ammunition supply point in the Northeast due in part to the disastrous sabotage and explosion at the nearby Black Tom Ammunition Depot in June 1916. Remembering the tragedies of Black Tom and the 1917 disaster in Halifax, Nova Scotia, many tri-state area residents and business owners vehemently opposed the idea of building a new ammunition terminal within New York Harbor, however the immediate need for an ammunition-loading terminal was so great in 1941 the order was issued—under a strict veil of secrecy—that Caven Point take up the additional role of handling munitions bound for the European and African theaters.

Though public knowledge about Caven Point’s additional duties would remain non-existent until the end of the war in Europe, the FDNY Marine Division was well briefed on the nature and scale of operations carried out at the facility. Every ship calling at Caven Point to load munitions was required to tender a copy of its blueprint and cargo hold plans to the Marine Division, so that in the event of an emergency, first responders could quickly and easily access, contain, and fight fires on any ammunition-laden ship. In addition to these measures, the U.S. Coast Guard maintained an active fire watch and sizeable fleet of pump-equipped patrol boats on a 24-hour alert around the pier, and the Bayonne Fire Department kept a fast reaction squad on alert as well. Every commercial tugboat calling the pier complex for ship-assist duties was required to have substantial external firefighting capabilities, to provide near-immediate response in the event of fire. Due in large part to these precautions, operations at Caven Point proceeded smoothly despite the hectic nature of operations at the now combined-use facility through 1942 and into 1943, when the buildup of men and material bound for England and Africa began to greatly swell the number of ships loading men, materials and munitions at the pier.

SS Alcoa Guide a near-sister ship to the SS El Estero and representative of how the El Estero likely appeared in April 1943.

One such vessel to call at Caven Point in April 1943 was the Panama-flagged SS El Estero, a 335-foot general cargo freighter operated by the United States Lines under contract to the U.S. Maritime Commission. Built in Staten Island as part of a three-ship class for the Southern Pacific Steamship Lines in 1920, the ship spent the first two decades of her service life engaged primarily in trade along the U.S. East Coast before being turned over to the U.S. government in June 1941 to help bolster the U.S. Merchant Marine Fleet. Though she was nearing the end of her useful service life, the ship was pressed into immediate service. By the time she came alongside the southeastern berth at the Caven Point finger pier, she was already a veteran of several harrowing trans-Atlantic convoy crossings, including the ill-fated Convoy PQ-13 in March 1942.

As a crew of U.S. Army stevedores made their way aboard ship and began to load the first of some 1,365 tons of mixed munitions from a string of railcars on the pier, the El Estero crew effected repairs to her aging and increasingly troublesome boiler system. By the time the last crate of ammunition was secured aboard, her hatches made ready for sea and the last of the stevedore work parties ashore on April 24, the El Estero had been joined at the finger pier by three other Europe-bound freighters. All three of her piermates were actively loading ammunition as her 5:30PM departure time drew near, and with a pair of tugs inbound to help pull her off the dock, El Estero’s engine room crew began light off her boilers to build up steam in preparation for departure. During this process an uncontained flashback occurred sending either a chance spark or a lick of flame into the ships bilges, which were filled with a thick mixture of oily seawater. Within minutes a fire had established itself and began to grow, filling the engine room with acrid black smoke. Realizing the gravity of the situation, crew quickly sounded El Estero’s fire alarm and set in motion what is considered to be the single greatest threat to New York Harbor—or any American city for that matter—during the entire of the Second World War.

This 1944 US Coast Guard photo was taken at the same location as the El Estero was berthed, and is representative of the environment at the pier on April 24th, 1943.

Word of the fire passed quickly from the El Estero to the pier, where a well-rehearsed response by the U.S. Coast Guard fire watch swung into action. Almost at once, a pair of patrol boats were onscene and ran hoses onto the ship while the Bayonne Fire Department dispatched two trucks and three engines to the ship. In spite of the rapid response, the fire burning deep within the ship showed no signs of abating and by 5:40PM the heat and smoke forced the evacuation of the ship’s engineering spaces and most of the below-deck midship areas. As the hope of a quick resolution went up with the now-thick plume of black smoke belching out of the ship’s air intakes, the sobering reality that the El Estero’s cargo could detonate at any moment came to grasp every person on the scene, only to be compounded by the fact that only feet away from the burning ship lay three other ammunition-laden ships and four full consists of ammunition-laden railcars. With a combined total of nearly 5,000 tons of explosives in immediate danger of being set off, a full-order detonation would have exposed most of New York Harbor, lower Manhattan, Brooklyn, Staten Island, Jersey City, Bayonne, and the strategically vital oil refinery-laden shores of New Jersey to a blast similar to a modern tactical nuclear weapon. With the progress of the Allied Mediterranean, North African, and South Pacific war efforts and the lives of thousands of civilians hinging on the successful containment of the fire aboard the El Estero, valiant Coast Guardsmen rallied volunteers to man the hoses aboard the burning ship and dispatched a call to the FDNY Marine Unit headquarters for urgent assistance.

From her position at Pier 1A in New York’s Battery, Fire Fighter’s crew had kept a trained eye on the ever-increasing pall of inky-black smoke rising over Caven Point, knowing full well there was a loaded ammunition ship on fire at the pier. Initial reports that the fire was being combated by onscene units were promising, but it was soon clear that the situation was taking a turn for the worse. Shortly before 6PM the order came to prepare for immediate action, and as her pilot came aboard with the plans for the El Estero tucked under his arm Fire Fighter’s engines rumbled to life and she was soon heading straight for Caven Point on what must have seemed like a guaranteed one-way trip.

Coming onscene shortly before 6:30PM both Fire Fighter and the John J. Harvey of Marine 2 took up positions on the starboard side of the burning ship. Their crews immediately passed hose lines up to the men on El Estero’s deck, lending substantial pumping capacity to the frantic effort to simultaneously cool the cargo hold ammunition and suppress the raging oil fire which was now totally out of control. Raising her aft tower monitor and sending a torrent of water down one of the engine room ventilation shafts, Fire Fighter’s crew were relieved to see a slight change in the color of the smoke coming from El Estero, a promising indication that the copious amounts of seawater were starting to have an effect on the fire. With their efforts soon coming under the direct command of Coast Guard Lt. Commander Arthur Pfister, a retired FDNY Battalion Chief and OIC of Coast Guard fireboats, efforts were mounted over the next half hour by firefighters and Coast Guardsmen to penetrate El Estero‘s superstructure and attack the fire from the inside with chemical suppressants, all of which were rebuffed by intense heat and poisonous smoke conditions.

With an explosion still perilously imminent by 7PM despite strident firefighting efforts, Captain of the Port Rear Admiral Stanley Parker issued the order that the El Estero be immediately scuttled. But with her seacocks located deep below decks and therefore rendered inaccessible by the intense fire, the order could not be carried out. A hastily convened meeting pierside among Lt. Commander Pfister, his counterpart Lt. Commander John Stanley, and commercial tug Captain Ole Ericksen led to the decision to get the El Estero off the Caven Point Pier, away from the other troopships, and out into the open harbor, where the effects of any explosion would be lessened for the surrounding area. A crew of twenty volunteers remained onboard the furiously burning ship under the command of LCDR Stanley to continue firefighting efforts. The commercial tugboats Margaret Olsen, Ola G. Olsen, George R. Randolph, and Beatrice Bush formed up at the El Estero’s bow, where they tied into a steel hawser and began pulling the powerless ship off the pier.

By the time the slow convoy began to make headway into lower New York Harbor, the rapidly setting sun revealed to shoreside onlookers the ominous orange glow emanating from what seemed like the entire length of the burning ship in the harbor. With the spectacle only serving to attract more curious crowds to windows and along the shoreline, officials were left no option but to break the silence surrounding the events playing out at Caven Point. Shortly after 730PM, New York and New Jersey authorities warned residents by radio and through local air raid wardens that an explosion was imminent and to take shelter indoors and away from windows.

Back out in the harbor, Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey split up and were now on either side of the El Estero as she was slowly pulled south towards Robbins Reef, with each fireboat pumping at maximum capacity through their monitors and deck manifold hoses into the El Estero’s holds. Making painfully slow progress against the inbound tide, the ships finally reached the shallows immediately off the Robbins Reef Lighthouse shortly before 8PM and both of the El Estero’s anchors were dropped in approximately 40 feet of water. With the last of the volunteer “crew” safely removed from the still-burning ship onto Coast Guard fireboats, Fire Fighter and the John J. Harvey directed their combined 36,000 gallons-per-minute pumping capacity into the El Estero’s holds in an all-out effort to sink the ship. Fire Fighter’s crew even went as far as utilizing her onboard air compressor and jackhammers to punch holes in El Estero’s hull to facilitate the flooding of her lower spaces. After another nervous hour of flooding efforts and several nerve-rattling low order detonations of deck-stowed fuel drums and ready anti-aircraft ammunition aboard El Estero, the efforts of Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey paid off as the ship finally took a list to Port and aided by several newly-added holes in her hull, flooded and sank to the bottom of New York Harbor with her decks and cargo holds completely awash shortly after 9PM. Fire Fighter and her crew stood by and continued to pour water onto the still-burning superstructure of the wrecked ship for another two hours, but by 9:45PM it was clear that the danger of an imminent explosion had passed.

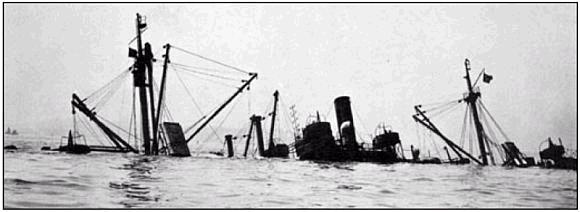

El Estero sunk off Robbins Reef the morning after the fire still flying her red “Baker” or hazardous cargo flag from her aft mast.

Released from her post shortly before midnight as the last of the visible fires aboard the El Estero were snuffed out, Fire Fighter and her crew returned to Pier 1A where personnel from the U.S. Navy were waiting to debrief them. With the official civilian “All Clear” broadcast only moments before she tied up at her berth, the veil of wartime secrecy quickly descended onto the evening’s events and the actions of the men aboard Fire Fighter and the other ships that saved New York Harbor. It wouldn’t be until 1944 that the first official mention and awards for heroism were bestowed on the men who fought the fire aboard El Estero; and for their part, Fire Fighter’s duty crew that day were honored as follows:

Pilot John A. Shearer – John H. Prentice Medal

Engineer Lawrence S. Gilliam – Henry D. Bookman Medal

Engineer Otto R. Kutzke – Albert S. Johnston Medal

Engineer Thomas J. White – Walter Scott Medal

Fireman Harry M. Biffar – Department Medal

Fireman Joseph F. Earney – Department Medal

Fireman Albert B. House, Jr. – Department Medal

Fireman Sven Victor Hull – Department Medal

Fireman Peter A. McNulty – Department Medal

Probie Samuel Braisin – Department Medal

It would take until August 1945 for the U.S. Army to reveal the true scope of what took place at Caven Point during the war, along with the full details of what took place on April 24, 1943.

As for El Estero, the ship that almost destroyed New York Harbor remained in her sunken state for another four months as U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and salvage experts decided on the best course of action for removing the still dangerous ammunition-laden hulk from the harbor. Eventually the decision was made to cofferdam the hull and raise the hulk without removing any of the cargo. In September 1943, the hulk of the El Estero was refloated and hastily towed out of New York Harbor to the open Atlantic Ocean, where she was set adrift and met her end as a live-fire target for U.S. Navy ships.

Refloated hunk of El Estero, it’s super structure wrapped in cofferdams, prepared for her tow into the Atlantic as a live fire target.

Due in large part to the secrecy surrounding the events of El Estero’s loss, her story remains largely unknown to the general public, but her untimely demise has left a very visible legacy in the waters around New York, specifically in Sandy Hook Bay. In August 1943, the U.S. Navy began high-priority construction of a new ammunition depot now known as Naval Weapons Station Earle which features a 2.9-mile pier designed to move the hazardous activity of loading and unloading munitions away from densely populated areas.

Further information on this event can be found at the following sites:

http://www.uscg.mil/history/articles/ThiesenElEstero.pdf

http://www.uscg.mil/history/uscghist/Port_Security_Photos_1.asp

http://www.usmm.org/msm.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_El_Estero